Augustus woodward

Here’s the story behind this historical portrait of Augustus Woodward. The original portrait is part of the Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society’s collection.

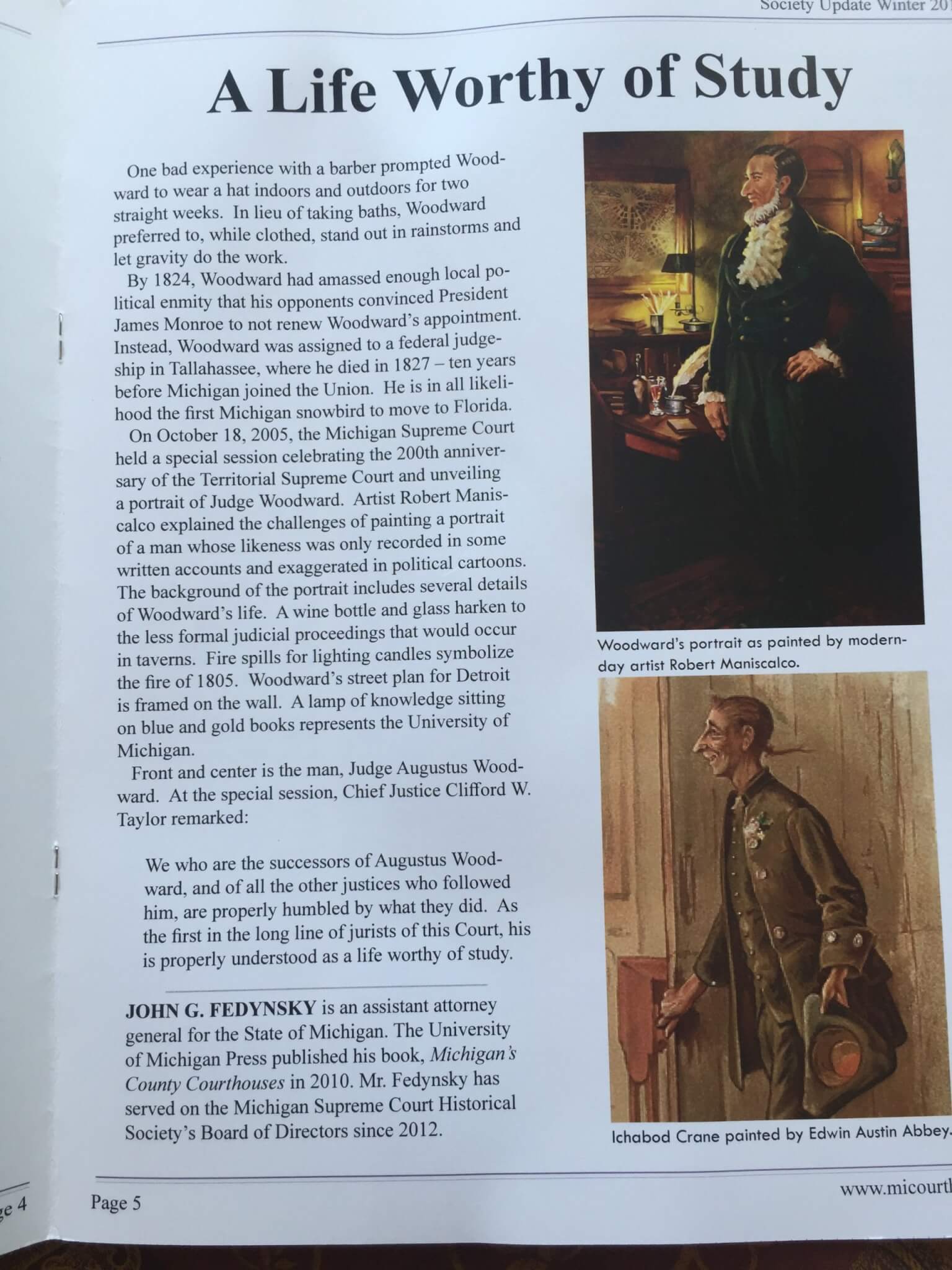

Although I have done a number of posthumous portraits in my career, this was a singular journey.Essentially, I reinvented the image of Augustus Woodward, from a political cartoon of him, which is the only known contemporary image made of him. His life is legendary.

Here is his story and the story of my researching him for this work of art.

See more of Robert’s posthumous portraits

View my informative slide show about the process to the right.

Here is the transcript from my presentation to the Michigan Supreme Court in 2005:

Mr. Chief Justice, Justices of the Supreme Court, and distinguished guests, it is my great honor to present my portrayal of Judge Augustus B. Woodward. May it please the court . . . for many years to come. I’ve been asked to share the most unusual story of my bringing this portrait into being. I would mention at this time that you all are invited to view a short slide presentation (above) illustrating the process following these proceedings in the reception area. I would also like to take a moment to acknowledge a couple of important people who have always been there for me. My sister Betsy, my wife Amanda (kids, Danny/Mary) and of course, my father Joe Maniscalco, with whom, I’m very proud to say, I hang in the halls of justice here at the Michigan Supreme Court.

Now, with regard to this painting, as with every portrait I paint, it was an exquisite adventure—a labor of love. To accomplish this particular result, however, I needed more than a flair with a brush, I had to become something of an historian. The project came about after the esteemed Justice Thomas Brennan presented what he called “a word portrait” to this court to mark the 300th anniversary of the City of Detroit, focusing on Woodward’s plan for Detroit as well as his appointment as Michigan’s first Territorial judge 200 years ago, making him the father of this great institution. In Justice Brennen’s “word portrait,” he noted the conspicuous absence of the real thing. Well, justice called out in response and, as the story goes, I was deeply honored to have been selected for this singular challenge. The rest is history.

As the court’s unofficial posthumous portrait painter I have been commissioned several times over the years to fill in the blanks, so to speak, of the impressive portrait collection housed within these walls. (whispered) I paint dead people. Who knows, maybe someday I’ll have the honor of being asked to paint a real live MSC justice! But I digress. Suffice it to say that as a result of the dedication of the Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society our state can proudly boast of having one of the most impressive and comprehensive portrait collections of any State Supreme Court in America.

My historical quest to find the real Judge Woodward began with Justice Brennen’s eloquent word portrait and ended in a place where Federalist architecture is exceptionally well-preserved: Charleston, SC. As an amateur historian, I embarked on several failed attempts at finagling myself into some of the great historic homes in Charleston. In one case I had to call on the aid of Angela Bergman, our esteemed Executive Director, who helped me gain access to the Charleston Museum collections, only to be disappointed when the period wasn’t exactly right and the conditions of my using the location were too limiting—in order to get what I needed I would actually have to handle some very precious antiques with my sticky, paint-covered fingers! For weeks I visited museums, law firms, fraternities, schools, plantation homes, restaurants, Inns, antique stores, tour homes; if anyone needs a recommendation of where to go in Charleston, just let me know! Finally, as it always goes, when hope was all but lost, I stumbled upon the perfect setting: The Thomas Elfe House on Queen Street, built around 1770, one of the oldest private homes in the Charleston peninsula. The proprietor, Bill Ward, a prominent collector of antiques from the period, was more than happy to assist me in putting together the authentic setting you see before you. All I had to do was wash my hands!

Meanwhile, I had to find the right person to play Woodward. After staging several impromptu lineups in grocery stores or at parties—several women suggested their ex-husbands as perfect for the part!—I found my man. Dr. Patrick O’Neill is the Director of Weight Management Center at MUSC. He happened to be the same height and build as Woodward; he was even a career bachelor, like Woodward. But most importantly, he was willing to play dress up with me. He towered over the desk and was perfect for the part, all decked out in a period costume, provided by Bruce Bryson of Theatrics Unlimited.

I took digital photos paying careful attention to lighting. I wanted to get the glow of the candle light and oil lamps used at the time. The rooms from the period were usually cramped and the front room of the Elfe House was no exception. I put my unwitting model through the ringer, experimenting with every conceivable pose I could imagine Woodward ever striking. I ended up with this simple, confident pose, which I believe evokes Woodward’s complexity and stature. Though he was known for his poor posture, I imagined he would have stood tall for his own portrait.

The painting features a number of significant artifacts that I’d like to touch on, if it please the court. All the furnishings and “props” included in the painting are authentic antiques from the Colonial and Federalist periods, what they call, “Adams-esque” in the south. In the background is a built-in cabinet and a mantle made by Thomas Elfe himself, a contemporary of Chippendale; his cabinetry and furniture are considered some of the finest of the period. A desk from 1790 anchors the composition and sets the stage for a number of historically significant features. Piles of books, a period quill, pewter ink fountain, indicia, wax and sander help to create a sense of his characteristic clutter. A notebook, which Woodward always carried with him, rests at his finger tips. An authentic wine bottle and glass suggest the less formal judicial proceedings of the day. The fire spills (used to light fires/candles, etc) in a container on the top of the desk represent the burning of Detroit. Woodward’s solution to the Detroit fire of 1805, his controversial “spoked” street plan for Detroit, is framed above the desk. And, of course, the lamp of knowledge, resting atop blue and gold books on the mantle over Woodward’s left shoulder is the symbol taken from the first seal of the University of Michigan, which he co-founded in 1817.

It is my sincere hope that this portrait helps connect us with our past, as it carries forward the story of the iconic, enigmatic, Augustus B. Woodward, who’s powerful contribution to our state, our country, our destiny secured his place in history. I want to personally thank and congratulate the Court and the Society and all of you who help bring these portraits into existence. It is because of your generosity that our history lives to inform us in the future.

Would you like to get inspiration in your inbox, rather than ads for more stuff? Welcome to ManiscalcoGallery.com

Would you like to get inspiration in your inbox, rather than ads for more stuff? Welcome to ManiscalcoGallery.com